Current Meeting Information for Our Members

January 26, 2021

March Fund Drive 2021 is Different This Year

March 4, 2021

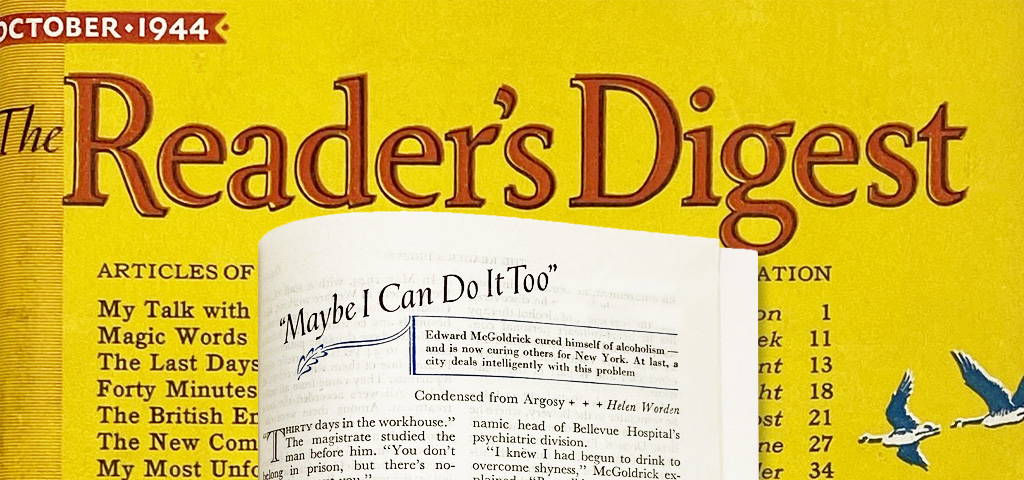

Edward McGoldrick cured himself of alcoholism –and is now curing others for New York. At last, a city deals intelligently with this problem.

Condensed from Argosy, by Helen Worden

“Thirty days in the workhouse.” The magistrate studied the man before him. “You don’t belong in prison, but there’s nowhere else to put you.”

Picked up as a drunk in a Bowery doorway, the 54-year-old prisoner, with twitching hands and sunken eyes testifying to a prolonged jag, was about to pay his ninth visit to Riker’s Island, New York City’s penitentiary. In another month he would be turned loose to drink again.

This was the way New York disposed of the alcoholic last year. Today it is different. Officially listed as a sick man, not a criminal, he is paroled in the custody of Edward McGoldrick, director of the city’s new Alcoholic Therapy Bureau. An attempt will be made to rehabilitate him by analyzing and treating the mental quirk which creates a craving for drink.

Director McGoldrick, 39, tall, lean, likable, will tell you frankly that he is an alcoholic himself, that for 15 years straight he was periodically in and out of sanitariums. Son of a state supreme court justice, he was a lawyer with a sizable practice when drinking began to dog him. Determined to find out the reason, he became a pupil of Dr. Menas Gregory, then the dynamic head of Bellevue Hospital’s psychiatric division.

“I knew I had begun to drink to overcome shyness,” McGoldrick explained. “By talking with me patiently and understandingly, Dr. Gregory brought that fear out into the open. Immediately it ceased to exist. Thereafter, because I wanted to be cured, my progress was steady – although I had to pass through the usual symptoms of recovery: shame, resentment and just plain jitters. I was occasionally tempted, also, to exhibit that terrific ego with which so many fellow sufferers cover up their feelings of inferiority.”

“Only one who understands from experience the hell these men go through can successfully head a bureau like this. Remember, I am – not was – an alcoholic.”

McGoldrick believes alcoholics must never forget they are allergic to alcohol, just as some people are allergic to strawberries or fish. “Once an alcoholic always an alcoholic;” and if they remember that, they are less likely to indulge in casual experimenting after they feel they have the craving under control.

While working on his own cure, McGoldrick helped also with Dr. Gregory’s more stubborn cases. To his amazement, he began having success – largely because he discovered that the real secret of alcohol therapy lies in heart-to- heart personal contact. “When I work with alcoholics,” he says, “my own example carries conviction and is part of the treatment.”

For a broader “clinical” training he went later to the Bowery, where he spent months with drunks and derelicts. Dressed like one of them, he slept in flophouses, ate mission handouts, exchanged confidences with those not too befogged by alcohol.

Early in 1943 McGoldrick decided to give up his law practice and devote all of his time to helping alcoholics. When Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia offered him the post of Assistant Corporation Counsel – an honor many a lawyer would covet – he turned it down. Then he explained his newborn project to the Mayor and found an eager listener. When he left City Hall, he was New York’s first alcoholic therapist. The Mayor had promised to back him unofficially for one year. The Alcoholic Therapy Bureau has now been given official status and operates under the Department of Welfare.

“We are not altogether altruistic about this,” the Mayor said to me. “Don’t forget that 80 percent of the cases in the magistrates’ courts are alcoholics. This means a terrific cost to New York.”

As the most fertile field in which to stalk the city’s alcoholics, McGoldrick picked the municipal lodging-house for the Bureau’s headquarters. The entire top floor was turned over to him and he begged chairs and desks from the city’s warehouse.

In May 1943, with a staff of two Department of Welfare workers, McGoldrick chose from city prisons, hospitals and courtrooms 100 human derelicts whose drinking pattern covered 15 to 44 years of chronic alcoholism, one of them with a record of 83 arrests. They came from all walks of life. All were accorded the same treatment. Among them were doctors, lawyers, engineers, reporters, actors, salesmen.

Twenty-five of the original human wrecks whom McGoldrick picked up fell by the wayside. But the remaining 75 are now solidly on their feet. Omitting, as not typical, the cases of 25 who started their reformation in the penitentiary, the records show that 36 percent of these salvaged derelicts never took a drink after McGoldrick picked them up, while 22 percent had one relapse and 42 percent had two relapses before winning their victory. All have jobs.

The main steps in McGoldrick’s cure are: restoration of faith, removal of fear, encouragement, renewal of social contacts and responsibility. Restitution should also be undertaken at the earliest possible moment; even though it be in tiny amounts, the alcoholic should start repaying those to whom he in debt. Let’s see how these principles are applied:

Bob, now 53 and long an alcoholic, had been working 14 years for a large corporation when his employer met him staggering in, and fired him on the spot. Then he took up drinking seriously. His heartbroken wife and daughter pleaded, threatened and finally walked out. Debts piled up. His friends crossed the street when they saw him coming.

At McGoldrick’s suggestion, Bob was put in the general ward – not in the alcoholic division – of Bellevue Hospital until he got over the shakes. Then McGoldrick visited him daily, encouraged him to “talk it out.” Like all drunks when they start sobering up, Bob was living in his past, full of his own degradation and shame.

At this stage, criticism of an alcoholic’s drinking only fixes the picture more firmly in his mind. He must be taken away from the past.

“Our object is to focus his attention on a healthy, happy future,” McGoldrick explains. “One o f the greatest blocks to reformation is fear of failure. In every victim’s subconscious mind lurks the memory of some failure – either in school, society, love or business. He fears that in making another attempt he may fail again. As soon as he believes that fate is working with, not against, him he has taken the first step toward restored self-respect. But you can’t preach religion to him. If he wants God, it helps, but it’s up to him.”

After Bob was sobered up, the Bureau helped him find a job – one which he could do well without too much effort, one in which he would not fail with the subsequent feeling of having lost his grip.

“At this stage there is an upsurge of self-respect and the patient’s moral inventory begins,” says McGoldrick. “Alcoholics are -usually trying to escape from something. Once they have faced it, they have nothing to run away from. I know. I found this out myself -and Bob found it out. He’s been going strong ever since.”

Tom, a former saloon owner whom McGoldrick had salvaged, talked freely of his past and present.

“I haven’t fallen off the wagon in nine months,” Tom said. “I couldn’t drink again. Not because of myself alone, but because of others. I’m coaxing four alcoholics along now. One is my brother. They might all go down without me.”

His clear brown eyes were serene. “I don’t have to fight myself when I pass a ginmill today. I never felt that way before. I’m staying sober because I want to. When you see an alcoholic like McGoldrick on his feet you think, ‘Maybe I can to it too.”‘

I asked McGoldrick if an alcoholic’s family could cure him. He shook his head. “Only under the most exceptional circumstances,” he said. “The relatives of an alcoholic suffer a special brand of humiliation, both before the public and in their own hearts. If, however, they have enough love and perseverance; if, instead of condemning him, they encourage him to analyze his drinking as he might analyze a disease, if they can make him realize how much they are depending on him; and if, above all, they are there when he needs reassuring, there’s a chance of a miracle. But if the average alcoholic’s family had the patience, compassion and realism to do this successfully, they probably would have saved their black sheep long ago.”

In the early stages of their cure the men seldom go outside the Bureau building without being accompanied by McGoldrick or one of the other cured alcoholics. Later, when he is on his own, if a man feels an impulse to drink he puts in a telephone SOS to McGoldrick or else rushes back to him. Seldom does McGoldrick fail to talk the man out of his desire. After one or more of these crises the patient usually finds himself able to handle temptation under his own power.

I asked McGoldrick if he thought one year was long enough to prove his case. “One month is enough if the alcoholic wants to be cured,” he said. “I known so-called reformed drunkards who, activated by fear or some other negative reason, had been on the wagon three to four years yet they were still far from being cured. You can look at my men and know they are not going to drink again – not because they are afraid to but because they don’t want to. The cure comes from within, and it doesn’t take a year to prove it’s working.”

The growth of the Bureau has made a separate building necessary and McGoldrick is just opening a three-story, 20-room frame house opposite the cool green of Bronx Bark. It looks like a private home or club. The ground floor has been converted into offices, dining room and kitchen. On the second floor are sleeping quarters – 20 beds – and a large sitting room, with radio, books and newspapers. There’s a lecture room on the third floor.

“We’ll have no doctor, no medication and no injections,” McGoldrick says. “We want to keep away from the institutional atmosphere. The men will make their beds and help around the house. Our only paid employees will be the cook and the building custodian.”

“There will be no attempt to cure alcoholics wholesale,” says McGoldrick. “They can’t be cured that way. Our system is more like the endless chain. One will cure four others, and these four will do likewise, until the city has an army of sincere alcoholic workers whose only recompense lies in seeing others get back on their feet.”

Asked how other communities, interested in establishing alcoholic therapy bureaus, could find suitable directors for similar organizations, McGoldrick answered, “Alcoholics Anonymous is a ten- year-old organization with 12,000 members and 50 branches scattered throughout the United States. All the members – and I’m one – are reformed drunkards. It has no dues, fees or officers, and its principles consist of 12 rules of living developed from the Ten Commandments.* Among the men in A.A. are many of the leader type. Since it takes an alcoholic to reform an alcoholic, I believe that’s where other communities will find directors.”

A postcard sent to P.O. Box 459, Grand Central Annex, New York 17, N.Y., will bring further information about this organization.

Source: Reader’s Digest, October 1944